Danga, Deshbhag o Udbastu Somoy: Paschim theke Purbobanga, Compiled, edited and introduction by Mridul Haque; Kolkata: Mandas Publication, 2024; Pp: 460; Price: Rs. 650; ISBN: 9789395065634

Danga, Deshbhag o Udbastu Somoy: Paschim theke Purbobanga starts with a summary of Dibyendu Palit’s short story Alam’s Own House. The use of this particular story by the editor is significant because it is a story in the crowd of many fictional narratives of partition, which has the migration from West Bengal to East Pakistan and its consequences as its subject which is also the core issue dealt in this book. Anannya Das writes.

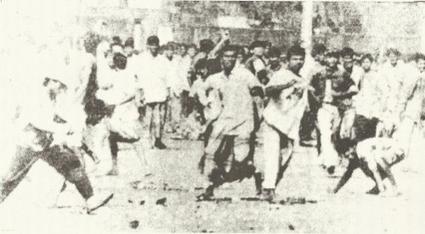

Michael Roper has stated how “personal accounts of the past are never produced in isolation from these public narratives, but must operate within their terms. Remembering always entails the working of past experience into available cultural scripts.” By using various oral narratives, fictional texts, magazine reports and statistical data, Mridul Haque has touched upon the riots of 1946, 1951 and 1964-65, the rumors created after the riots and what the Muslim population went through after them, to show how it propelled the feeling of homelessness for the community in one’s own birthplace and ultimately led to many migrations. The last section of the introduction is a question- “Where are the narratives of East Bengal in the study of partition?”(“পার্টিশন অধ্যয়নে পূর্ববঙ্গের বয়ান কোথায় তাহলে?”).

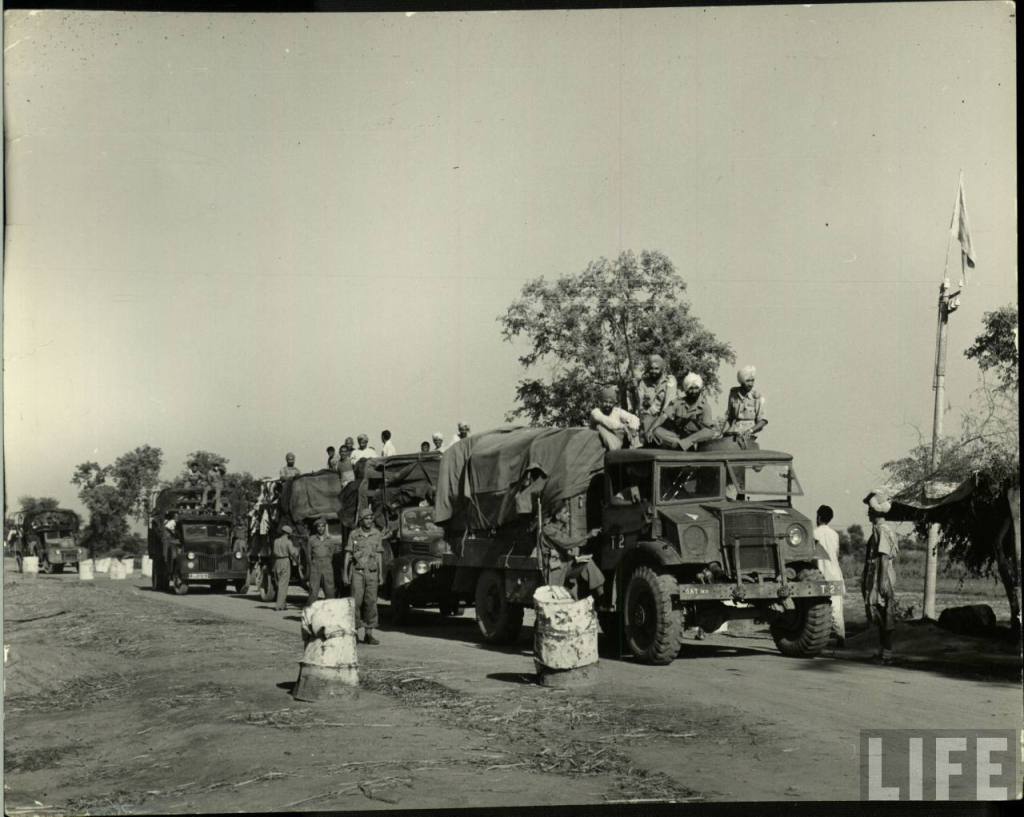

The major three reasons which are discussed with detail and examples hereafter are- firstly, the dream of having a land solely based on Islam and the expectation of getting more opportunities there as Muslims than they would get in India as new minorities made many families to choose to go to East Pakistan. Secondly, for many Muslims, the journey from West Bengal to East Pakistan was thought to be the Hijrat [journey to the promised land]. Thirdly, their linguistic identity [Bengali speaking] became a ‘barrier’ for them in having a concrete identity in the new land. This choice, hope of religious attainment and duality of identities were what the migrants were faced with more than the trauma of leaving home or physical violence.

The book, as mentioned before, has used both memoirs and essays in its methodology to find out the events and various concerns regarding the west to east migration. The compiler and editor has started with seven memoirs to bring out stories of individual migrants which got suppressed by the larger narratives. The first one is narrated by Saiyyad Anwar Ali whose route of migration was from Bashirhat to Kajimohalla. Their family fell into the category of ‘optees’ and faced no material loss and suffering as most refugees did. This particular memoir is significant to the book as it gives snippets of the consequences of the decision of Lord Mountabtten to declare the border division two days after independence and the failure of Cyril Radcliff who included the Muslim majority province of Bashirhat into India. The resistance of a woman [narrator’s mother] at the face of extreme crisis and the now ‘ancient’ communal harmony which ultimately saved their family are the things worth noting from this narration as it depicts the dismantled situation and relationship of the two communities.

The second memoir is not narrated in the first person. Sumit Das, the narrator, is crucial as he witnesses the transformation of Khanpur into Netajinagar and the conversion of mosques into Hanuman temples, reflecting the shifting identities of the central character as a migrant. This change was triggered by the riots following the 1963 Hazratbal Incident, which led to the burning of Abdur Rajjak’s house in Khanpur and their subsequent migration to East Pakistan. This narrative highlights the hardships faced by minorities in Kolkata during the 1964 Calcutta riots. The memoir traces the journey of a refugee who, starting as a school play participant, returns as a star in Bangladeshi and Bengali cinema, using acting as a means of survival from his time in a refugee camp.

The third account, by Hassan Ajijul Haque, interprets the partition through the eyes of a child who celebrates it and participates in parades, unaware of its true impact on his community. The child’s innocent excitement at school functions contrasts with the apprehension of village elders, party members, and his family’s serious discussions about the country’s division.

The following memoir by Saiyyad Anwar Ali sheds light on the forced occupation of Muslim homes due to the influx of migrants from the eastern side of the border to the west. This compelled many Muslim families, including the narrator’s grandmother, to migrate to East Pakistan. Despite her determination to stay, she eventually had to leave when individuals from Khulna forcibly took over her house. The account illustrates how Muslims suddenly became a burden on Indian lands. Maitreyee Devi’s memoir discusses the role of newspapers, magazines, and literature during the partition in fueling communal hatred towards Muslims in West Bengal. It highlights the efforts of intellectuals, including herself, to counteract this animosity by creating magazines like ‘Nabajatak’ and other literature. Additionally, it points out the lack of reporting on the attacks against minorities in Bengal, contributing to the biased perception of the riots. Lastly, Ahmedi Begum narrates her struggles after the Calcutta riots of 1946 when she was six years old, depicting how her family became homeless in their own city, lived in a rented house, and eventually had to migrate. This mirrors the experiences portrayed in M.S. Sathyu’s “Garam Hawa,” where the Mirza family faced a similar fate.

The book consists of ten essays by different authors who have penned down various sides of the west to east migration by taking up different themes, events, specific places or particular sections of society. The first essay titled ‘Muslim Udbastu O tader Abhiprayan Bittanto: Ek Onyo Deshbhager Golpo’ (‘Muslim Refugees and their Migration Chronicles: A Different Tale of Partition’) by Anindita Ghosal highlights the segregation the Muslim refugees from West Bengal faced in the hands of the native Muslims of East Bengal. As mentioned in the introduction, the refugees did not get their “land of eternal eid” and struggled to create a definite identity there after migration. She divides the refugees into optees, skilled refugees, true ‘bastuharas’ or homeless refugees staying in refugee camps or other temporary settlements and Bihari Muslim refugees. Like the second essay ‘1947 er Banga Bhanga: Malda- Murshidabad o Rajshahi Jelar Seemana Chinhitokaran o tar Probhab’ (‘The 1947 Bengal Partition: the Demarcation of Borders between Malda, Murshidabad and Rajshahi and its Effect’) by Dr. Md. Mahboor Rahman talks about how the Bihari migrants created a life for themselves by taking up different vocations and contributed to the informal economy of Rajshahi, this essay shows another side of the Bihari migrants as they were preferred by the central government of Pakistan for being Hindi or Urdu speaking in getting properties (left by Hindus) lands and jobs.

The third essay of the book is written by Arupkumar Das and is called – ‘Deshbhager Bastob o Golpo: Onalokito Andhare Alokpaat’ (‘The Facts and Fiction of Partition: Throwing Light to Darkness’) brings the stories of the margins to the centre in the context of partition. It substantiates the lower classes [irrespective of being Hindus or Muslims] to be the section who suffered the most after partition and shows how the events were just a change of hands of power between the influential part of the society and nothing really changes for the subjugated and the oppressed.“কি যে হইলাম খোদাই জানে.। আগে চাষ করতাম চৌধুরীবাবুগো জমি, পরেও হেই জমিই চাষ করলাম, এহন তার গালিক সফির মিয়া, ফারাক তো দ্যাখেন খালি এই” (“Only God knows what we have become. Previously, we used to work in the land under Chowdhury Babu, after that we are working on the same land just under Safir Miya, I do not see any difference other than this”) – strengthens the author’s argument.

Abdul Kafi in ‘The Book of Silence and Partition Literature: the Eternal Division of the Self’ deals with subjects like inclination towards the past, the importance of post-memory in knowing about partition, the use of the capital ’P’ which renders the event as not only the division of one nation but the split of identities and lives forever, the scuffle between “manufactured silence” and the silence created by trauma of partition, the importance of remembering the event in present times etc. The general notion about East Bengal after partition has been that it is a place which was forsaken. Sayeed Firdaus in ‘1947 er Bangla Bhag: Bharot Kendrikotar Poropare’ (‘The Bengal Partition of 1947: Shifting focus from India’), has shown how the migrants from west to east saw East Bengal as a place of new hopes. It emphasizes the almost unexplored duality and dilemmas faced by the Bengali-Muslim migrants to East Bengal between their Muslim and Bengali identities- a discussion overshadowed by the histories of east to west migration.

The next four essays talk about specific riots or migration from or to a specific place and provide new perspectives about those. Like the essay ‘1964 Saaler Danga, Hindu-Muslim Somporko o Ganamaddyomer Bhumika’ (‘The Riot of 1964, Hindu-Muslim Relation and the Role of Mass Media’) Ifaat Ara has presented such a picture of the 1964 riots which was missing from the popular narratives of the event. It includes instances of resistance and attempts at peace making by common people, leaders, the press, students and the intelligentsia of East Pakistan. Likewise, Muntasir Mamun and Murshida Binte Rahman in the essay ‘Purbobonge Ponchaser Danga o Poshchimbonge Protikriya’ (‘The Riot of 1950 in East Bengal and its Reaction in West Bengal’) has shown how properties and in effect lives were exchanged between migrants which resulted into new names and identities based on the place they have migrated from, after the Riot which ignited in Kalshira of East Bengal.

Md. Ahsan Habib in ‘Saatchollisher Deshbhag o Jalpaiguri- Panchagorer Migration: Samajik-Sanskritik-Orthonoitik Probhab’ (‘The Partition of ‘47 and the Migration of Jalpaiguri-Panchgarh:Socio-Cultural-Economic Effect’) has gathered images of a migrant’s struggle and assimilation into a new socio-cultural reality by studying various articulations by migrants like verses and songs (Holir Gaan) etc. The history of the communal riots of Bengal together with the history of the place of Darusha has contributed in the search of the cause of a riot there in the year 1962 which is found out to be the tactful divergence of the Hindus to make space for the newly arrived Muslim immigrants there. The ghettoization of Muslims native to Kolkata after partition is what Anwesha Sengupta has discussed in her essay titled ‘Deshbhag o Kolkatar Muslim Somproday: Sonkhaloghu Hoye Othar Itihas’(‘Partition and the Muslim Community of Kolkata: the History of Becoming Minorities’). She has shown how the spaces of religious importance to the Muslims like Mosques, Dargah, Madrasas, even graveyards of the city were annexed by Hindu refugees and the Muslims (the weaker sections of Muslims who did not have the means to migrate) were thrust to a few pockets in Kolkata, hence making them internal migrants. She shows how not only the properties, the Hindus took over the Muslim businesses as well, making them powerless in every sector and forcing them to live as an inferior section of the society.

The book has used both qualitative and quantitative methods of research in order to delve deep into the yet not adequately explored west to east migrations after partition. It has opened new windows of perspectives by discussing the riots from the point of view of the migrants on the other side of the border. The book is significant as a record of the distinct struggles as well as changes that the migrants to East Pakistan went through in terms of cultural assimilation, religious and linguistic identity crisis, segregation, professional alterations, sense of homelessness etc. Not only this, this book has touched upon subjects like post memory and internal migration which opens up broader lanes of research on partition. The book however has not allotted enough space to the present situation of the migrants and refugees in their specific places of migration. Yet, it is an important book to understand the current attitude of the two communities towards one another by studying their long history of harmony and disharmony since partition.

[Cover Image: Book cover]

Anannya Das is a Masters in English Literature and Language from the University of Calcutta with research interest in partition studies, migration studies and memory studies. Anannya maybe reached at anannyadas05@gmail.com.

Leave a comment